James 1:17-18, 21-22, 27 ‘Pure, unspoilt religion… is this: coming to the help of orphans and widows… and keeping oneself uncontaminated by the world.’ (James 1:27) A few weeks ago a fellow priest was filmed on a programme about pilgrimage while making the following statement; ‘I am not religious’. This was a last-ditch attempt to spark a meaningful conversation about faith with another pilgrim, but the contentious nature of that phrase remained the same – a priest of the established Church of this land said, ‘I am not religious’. The whole incident was rather telling; not so much about the priest speaking, but rather about how society views people who might describe themselves as religious. Being religious can be misunderstood as a bad thing; as an alternative description for either being blinkered, or outright killjoys with fundamentalist tendencies. And if that be the case – most definitely – who would want to be labelled as “religious”? This morning we begin to explore the Letter of James. In writing this letter the Apostle James had in mind a Christian community formed by both long-standing, paid-up, members who needed a little refreshing course, as well as by people who stood on the fringes – sort of half-way in and half-way out of the Church – those who couldn’t quite commit themselves to be “religious” in the Christian sense. Sound familiar? James’ Church is our own Church too, in many respects. Every church community will have both those who attend Sunday services religiously (that word again!) and then forget about God for the other 167 hours of the week, as well as those who would put themselves down as Christians on a census form, but who would come to Mass once or twice a year tops – and, of course, everyone in between. Common to both of these groups is their unwillingness to let the Christian faith actually shape the way in which they live. And to both of these groups James writes a simple set of instructions, a basic guide on how to be a Christian and on what it means to be religious in the way God intended for us to be. The passage we encounter this morning starts from the very beginning saying that it is not good enough for Christians to listen to God’s word and then do nothing about it. James affirms that if this is our attitude towards Christianity and the Church, this just won’t do; in fact, he says, we are deceiving ourselves (Cf. James 1:22). This type of faith will not save us. Instead, he says, as believers we have to do something, we have to be “religious people” – that is, not narrow-minded individuals, but those who act according to God’s instructions and God’s example. But what are these instructions? We find a clear one at verse 27; ‘coming to the help of orphans and widows’. As James puts it, God chose each one of us to be his own beloved child in the Lord Jesus. God made us his children in the waters of Baptism. Consequently, as his children, we are called then to do the same works of God our Father does. In the Scriptures God is described as the defender of those who do not have anyone to plead their causes – represented by orphans, widows, foreigners, and people on the margins (Cf. Psalm 85:5). Then, if God our Father does these things, we are to do the same, just as children learn core behaviours by imitating what their parents do. Christian social action becomes part of the way we worship of God; and the way we treat the least in our society becomes the measure of whether we are “religious” or not. The second instruction we find is to remain ‘uncontaminated by the world.’ As James puts it, our social environment and the wider community we live in are instrumental in forming our characters – and quite often not in a good way. Because of the bad things we experience and the evil that we may endure, over the years, we could change, becoming more cynical and selfish, less disposed to do good, and increasingly blind to the needs of others. But this, James says, should not happen among Christians. God our Father is not influenced or contaminated by the world, nothing can sway him from his generosity and his purpose of doing good… we read, ‘with [God] there is no such thing as alteration, no shadow of a change’ (James 1:17). Therefore we – his children – must make sure that nothing in this world could poison our hearts with bitterness and cynicism. ‘Pure, unspoilt religion… is this: coming to the help of orphans and widows… and keeping oneself uncontaminated by the world.’ Being religious is not a call to be fundamentalists or to be narrow-minded people. In the Christian sense, being religious is a balancing act between worship in church and doing good in the world. It is a loving response to God for choosing us to be his children; the way in which we imitate our heavenly Father, and the way in which we grow into the likeness of God. All this is summed up in one verse from Jesus in Matthew’s gospel; ‘Be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect’ (Matt 5:48).

0 Comments

Text: John 6:60-69

‘After this, many of his disciples left him and stopped going with him.’ (John 6:66) We often read together stories from the gospel where the Lord Jesus is revered, sought by many, and listened to. When we hear of opposition, this generally comes from outside, from the people who do not accept him and look for to his demise. John 6 – which we finish today – has so far fitted into these parameters. Jesus has worked miracles, he has been pursued by the crowd who even wanted to make him king by force (Cf. John 6:15), he has taught countless people and he has revealed himself as ‘the living bread that came down from heaven’ (John 6:51). Whilst opposition has come from the usual places and it was summarised last week in a simple question, ‘How can this man give us his flesh to eat?’ (John 6:52). However, as we reach the end of the Bread of Life discourse we encounter something different – an unexpected turn of events where both openness and opposition to Jesus come from among the same group, from among his disciples. The reading picks up from where we left it last week and says, ‘After hearing his doctrine many of the followers of Jesus said, “This is intolerable language. How could anyone accept it?”’ (John 6:60). The disciples hear Jesus saying ‘my flesh is real food and my blood is real drink’ (John 6:55), they hear him talk of his body as the Bread which give life to the world (Cf. John 6:51), and they are stunned by these words. A rift opens among them. On one side, many disciples – not one or two, but “many” – are sceptic about how Jesus could ever give his own self as food, and they brand his teaching as “intolerable language” – in other translations this is rendered as “unacceptable saying”, or a “hard teaching”… On the other side, we have Peter and the other eleven disciples – whom, far from being perfect, trust in the Lord’s word and remain with him. The rift among the disciples hangs on this; Jesus said, ‘Very truly, I tell you... Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day; for my flesh is true food and my blood is true drink’ (John 6:53-55). Think about it. Of course this is could be seen as an unacceptable saying. Many disciples thought they were following a religious leader who would have restored freedom to the people of Israel with his revolutionary ideas. But what they hear now from him is a speech about giving himself up as food and drink to those who believe… What on Earth could this even mean? As a consequence, the gospel tells us, a good number of disciples leave Jesus – they literally do the opposite of conversion; they turn away from him – and stop travelling with him. The words of Jesus plunge disciples into crisis, and still to this day the Bread of Life discourse is the stumbling block for many Christians. The teaching about the Sacrament of the Eucharist, about Jesus’ Body and Blood, has become a visible rift within the Church for the last 500 years at least – but it has been present since the very beginning. The fact that Jesus is present on our altars with his Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity is an unacceptable doctrine for many but the cause of hope, consolation, and joy for others. It all depends what side of the divide we decide to go for. ‘The Eucharist is the place where one comes to eternal life. Encountering the broken flesh and the spilled blood of Jesus, “lifted up” on the cross (vv. 53-54), [we] called to make a decision for or against the revelation of God in that encounter (vv. 56-58), gaining or losing life because of it (vv. 53-54)’ (F.J. Moloney, The Gospel of John, p. 224). The words of Jesus may be a difficult saying to understand, but that should not be an obstacle to faith. Jesus calls us to believe in him and in the mystery of his Body and Blood, not to have a PhD in sacramental theology. Therefore, when he says to us ‘my flesh is true food and my blood is true drink’ we have a straightforward choice. We can stubbornly rely on ourselves and our cynicism, believing only what we can prove or understand (like the many disciples did), or we can courageously embrace the faith, aiming to rely solely on the Lord Jesus and on his words no-matter-what – never ever letting go of him. It could be that the Lord Jesus is addressing us today as he did to the Twelve, ‘What about you, do you want to go away too?’ (John 6:67). But, through Saint Peter, the gospel gives us the words with which we should answer him. Kneeling at the altar rail to receive the Body and Blood of Christ it is as if we were saying, ‘Lord, who shall we go to? You have the message of eternal life’ (John 6:67). Text: John 6:51-58

[They] started arguing with one another: ‘How can this man give us his flesh to eat?’ (John 6:52) In 1263 the small Italian town of Bolsena became the backdrop for one of the most famous miracles of the Middle Ages when, in the ancient church of Saint Christina, the consecrated host inexplicably began to bleed during Mass. The host, the Bread of the Eucharist, bled over the priest’s hands and over the corporal – the square linen placed on the altar. The corporal stained with Lord’s blood was taken to the city of Orvieto and enshrined as a relic in the cathedral where it attracted both pilgrims and sceptics who wanted to see this wonder for themselves. Almost 800 years later that corporal is still there on display; still the cause of much devotion for believers and of speculation for sceptics. Perhaps more remarkable (and relevant for us) than the miracle itself is the back story of the priest who was celebrating Mass when all this took place; the man whose hands were touched by the blood flowing from the host. He himself wasn’t the stuff of miracles or a famous wonderworker; he was just a pilgrim on his way to Rome named Peter of Prague. He was devout and committed priest but, as the story goes, Pater also harboured doubts that the Lord Jesus could be truly present in the Sacrament of the Eucharist. And so, this miracle that touched him so literally was soon perceived by people as God’s own intervention to restore the faith of one of his doubting servants. But it didn’t stop there; news of this baffling event spread like wildfire and the Miracle of Bolsena became the cause of much devotion and catalyst for renewed faith in the presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. Today the lectionary presents us with the most important instalment of the Bread of Life discourse from John’s gospel. And as we listen to the Lord Jesus saying, ‘I am the living bread which has come down from heaven’ (John 6:51), we too might start to feel a little like Pater of Prague. In fact, we might be tempted to dismiss the entirety of John 6 as nonsense or as a convoluted metaphor, by echoing the words of Jesus’ opposers who say, ‘How can this man give us his flesh to eat?’ For three-quarters of the Church’s history the vast majority of Christians have believed that Jesus comes to be really and truly present in the Sacrament of the Eucharist; have believed that the bread and the wine offered on the altar are permanently changed into the Body and Blood of the Lord; and have believed that through participation at the altar (by receiving Holy Communion) soul and body are nourished with Christ himself. Then came the various waves and controversies of the Reformation, and with them arrived terrible confusion for the average person in the pew as well as doubts about the presence of the Lord Jesus in the Eucharist. Ironically, it was precisely those reformers who advocated a form of Christianity based simply on literal teachings of the Bible who brought many Christians to doubt the very words of Christ himself and to ask sceptically once again, ‘How can this man give us his flesh to eat?’ The result of this dreadful confusion is that so many devout and committed Christians nowadays harbour doubts like Peter of Prague; so many are left confused. They stay away from the Mass, regarding Holy Communion as an optional extra, rather than a necessary, personal, and intimate encounter with the Lord Jesus. A repeat of the Miracle of Bolsena would be a great blessing from God, and it may help Christians to recover faith in the Eucharist. But where would it leave us in the long run? Do we really need another Eucharistic miracle in order to reaffirm the belief that Jesus is present for us on the altar? The truth is that we don’t. If we needed miracles, then God would provide them. We have something greater than miracles here; we have the word of the Lord Jesus… and if we can’t trust the word of Christ, who could we trust? ‘How can this man give us his flesh to eat?’ People might ask, but to this question Jesus simply and unequivocally replies, “the bread that I give is my flesh for the life of the world” (Cf. John 6:51) and, ‘my flesh is real food and my blood is real drink’ (John 6:55). Whenever we approach the altar rail at Holy Communion, or whenever we approach the tabernacle, Jesus is there for us – Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity. The one who loves us, is here for us. The one feeds us, is here for us. The one who saves us, is here for us. Though the lowliest form doth veil thee as of old in Bethlehem, here, as there, thine angels hail thee… …here for faith's discernment pray we, lest we fail to know thee now. Alleluia! Alleluia! Thou art here, we ask not how. (from Lord, enthroned in heavenly splendour)  By Mother Janet Yabsley - Text: John 6: 24-35 Jesus answered, ‘I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry; whoever believes in me will never thirst.’ (John 6:35) It was a difficult time to be living in the East End of London in the early 1940’s. A time when the daily effects of war had been continuously wreaking havoc on its population for many months. But my family, who had lived there for several generations, decided to remain in spite of the troubles. First of all my father was a firefighter in the London Fire Brigade. He had volunteered and needed to be there. From my mother’s perspective, a brief period of evacuation in the peaceful countryside of Wales had proved to be much too quiet for her. Being out of touch was making her anxious, so she brought me back to our home where we could spend at least some time with my father. Life was far from easy, but community cohesion, friendship, support and helping one’s neighbour were right at the top of the list of things people could do for one another. Many adversities brought people together. Luckily our home escaped damage, but others - on all sides of the conflict - were not so fortunate. During the bombing raids of WW II thousands of children were orphaned and left to starve. Some were rescued and placed in refugee camps where they received food and a level of care. But many of these children had lost so much that they couldn’t sleep at night. They feared waking up to find themselves once again homeless and without food. Nothing seemed to reassure them. Then someone had the good idea of giving each child a piece of bread to hold at bedtime. Holding their bread, the children could finally sleep in peace. All through the night the bread reminded them, ‘Today I had something to eat, and I will eat again tomorrow.’ The knowledge that still today there are people who find themselves in the same predicament as those children, raises questions for us. They are not questions exclusively for Christians but they do affect us acutely when we ask them in the light of the gospel. What problems beset Christians living in a materialist society? What are the true needs of those who seek after Jesus? How do we understand the ‘spiritual’ in our own abundance? In the relative comforts of life here in the West we are largely buffered against the harsh realities that millions suffer today. In the protected atmosphere of my own living-room I can choose to put away my newspaper or turn off the T.V. whenever images of conflicts and disasters of all kinds, demand my attention. Unless I physically, bodily enter into the situation, I cannot truly grasp its reality. I may feel a number of emotions - shock, pity, anger etc. I may also experience an acute sense of impotence, for at its core the problem is always a political one. There is hunger and destitution for some because others are greedy, or corrupt, or both. Christian social responsibility demands that the issues are addressed in concrete terms, but nothing will change while nations cannot live in peace with one another. Greed, and yet more greed, is always lurking nearby. (Cf. James 3:16-18) The question of greed is never far away in the gospel accounts of Jesus’ miraculous feedings. As he leaves the scene they follow him - even hound him. They are greedy for yet more miracles. They hope to see some kind of spectacle, but know nothing of his true purpose. Jesus says to them, ‘You are not looking for me because you have seen the signs, but because you had all the bread you wanted to eat.’ (John 6:26) What Jesus does is never a magic trick but rather a sign of God’s love for them, tangibly demonstrated. They have not yet understood the symbolism in his actions. It is frequently mentioned that Jesus uses Barley loaves, the bread of the poor. One of the first miracles concerns a poor woman who begs for mere crumbs - crumbs that drop from the table to the floor. She will be satisfied with them if her daughter can be made well. Her need is not for bead to eat, but the nourishment that Jesus gives from his capacity to listen, to hear, to understand and to heal every kind of infirmity. (Cf. Mark 7:25-30) The demanding attitude of the crowd is set against the ancient traditions concerning hospitality. Jesus, who had compassion on them, adhered closely to the tradition. First, the people were made to sit down. Then there were conversations, teachings and prayers. Then the food was set before them and they ate. Spiritual needs were satisfied before the needs of physical hunger (Cf. Mark 6:34-42). First of all, to eat bread, in its deepest meaning, is to taste the very source of all bread and nourishment which is the true and living God. For it was God who created the earth, all living things, all food upon which we depend. Yet we do not live by bread alone but by every word that comes from the mouth of God. (Deuteronomy 8:3) Out of the mouth of God comes the creative word that makes all life, and nourishment possible. In the beginning God spoke, and it was so. Jesus said a prayer of blessing before he shared the loaves, acknowledging God to be the source of all nourishment, and so conveying to the people the need for a spiritual response to God’s acts of supreme generosity. The God of life has made all things holy - a reflection of the Divine Holiness - therefore all creation is to be revered (Cf. Genesis 1:29-31). The Christian life is not simply a ‘natural religion’ of thanksgiving for creation, and of good deeds. God, who is Love, has made us a holy people, a redeemed people; accepts our service and our worship. Our prayer confirms and deepens our existing relation of intimate trust between God and ourselves. When Jesus talks about bread in the gospels, the tradition of breaking bread as an act of worship is a strong undercurrent. Of course the Last Supper has not yet taken place - we are only at chapter 6 - but the gospel of John brings these ideas clearly into focus, for the community from which his gospel comes, already had the sharing of bread at the centre of its worshipping life. What we read was set down in writing, in the light of the experience of early Christians (Cf. 1Cor. 11:25-26). In all four gospels Jesus blesses bread, divides it and shares it among the people. In the crucial words we heard this morning Jesus declares himself to be the true bread. ‘I am the bread of life.‘ In other words, “I, in myself, am true bread, true life.” Jesus, within the bond of covenant with his heavenly Father, is true life; and so can bring about a condition of eternal life in those who feed upon him. Real bread is spiritual, for the followers of Jesus and indeed for all humankind. Yet Jesus will later remind some of those standing nearby that they have seen him and yet do not believe. (John 6: 36). The Eucharist - a Greek word meaning ‘Great Thanksgiving’, with its Latin equivalent the Mass, meaning ‘Great Feast’ - is always a celebration of the new humanity, the ‘community of gift’ between God and human beings, and between human beings themselves. The new community are to take Jesus Christ as their pattern - in lowliness of heart; in their hunger and thirst for justice; in their compassion; in their role as peacemakers; in their capacity for costly giving of themselves (Cf. Matthew 5:3-12). At the personal, individual level, discipleship means daily seeking to draw closer to Jesus, to learn of him, trust him, and thereby to trust in God (Cf. Matthew 11:28-30). I would like to share something with you that I find helpful, although you may of course have something of your own that you do in your own way. Perhaps then, later today, in a quiet space, ask yourself this question: “For what moment today am I most grateful?” Think about that for several minutes. Then ask, “For what moment today am I least grateful?” See where those questions lead you. ‘Speak, Lord, for your servant is listening’ (1Sam. 3:10). Amen.

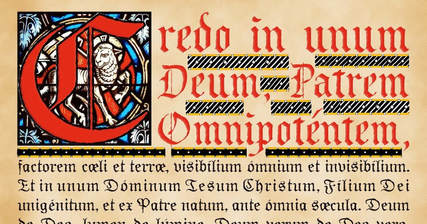

Ephesians 4:1-6 There is one Body, one Spirit, just as you were all called into one and the same hope. (Eph. 4:4) Over the last Sundays we have been reading the Letter to the Ephesians which speaks to us about God’s desire to restore and gather up all things in Christ. It is in the context of this divine plan that we are able to discover our true identity as adopted sons of the Father, who sees each believer in that ‘one new single New Man’ (Eph. 2:15) the Lord Jesus creates within himself. In other words, Ephesians tells us that we are one with Christ, and, because of this, we are worthy of the same incredible love the Father lavishes on his only-begotten Son. Today St Paul continues on the theme of oneness by articulating how our sense of unity in the Lord Jesus should influence the way we relate to other Christians. Oneness with Christ and oneness with other believers are indissolubly linked due to the simple fact that we are all members of the same body. This is a recurring concept in Paul’s letters. To the Galatians he writes, ‘there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus’ (Gal. 3:28); to the Corinthians he says, ‘we were all baptized into one body – Jews or Greeks, slaves or free’ (1Cor. 12:13)… and, when talking about Holy Communion, he also adds, ‘The bread that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ? [Therefore] Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread’ (1Cor. 10:16-17). Oneness in Jesus destroys all barriers among believers and unites us together into the ‘one single New Man’, the one body of Christ. In this sense, oneness means that, as Christians, we all belong to one another, regardless of our quarrels, schisms, and theological differences. If we understand this, then, a deep sense of wonder should pervade the way we look at each-other as Christians – and particularly so when we look across denominational divides. Yes, we are different. Yes, oftentimes we can agree on very little. Yet, in the words ‘one Lord, one faith, one baptism’ (Eph. 4:5) we are one. So it should not come to us as a surprise (or a historical fluke) that each Sunday we still say in the Creed, ‘We believe in one… Church’. We do not say, “We believe in a church that sometimes gets things horribly wrong”; we do not say, “We believe in the Church of England”; and we do not say, “We believe in a church founded by Henry VIII or Elizabeth I”. To say ‘We believe in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church’ is an act of faith in as much as we believe that the body of Christ transcends denominations; it is an act of hope as we look forward to a time when the full and visible unity of the Church will be restored; and it is an act of humility in as much as we affirm that, as Christians, we all of equal value as members of the same body. ‘There is one Body, one Spirit’, says Paul. Then, how are we to act in response to this belief that we are all one in the Lord Jesus? How are we to express oneness in the face of so many centuries of Christian divisions? Paul’ advice to us may seem a little vague but it is rather practical. He says, ‘bear with one another charitably, in complete selflessness, gentleness and patience’ (Eph. 4:2). This means that we should accept and welcome other Christians through love – but not just any type of love; “charitably”, meaning through perfect love. Easier said than done, I admit that, especially when we live in a society where people are often expected to assert individuality and independence over, against, and even at the expense of others. But my guess is that Paul is also aware of this difficulty al well. By saying ‘bear with one another’, keep the peace, and ‘preserve the unity of the Spirit’ (Eph. 4:3) the apostle starts from the bare minimum. Paul encourages us to at least be aware of the Christ’s presence in the other when we meet with other believers and to acknowledge this presence through actions and attitudes inspire by love. The bottom line is quite simple. The Father loves us in seeing Jesus in us, so we too must love others by endeavouring to see Christ in them.  Ephesians 2:13-18 To create one single New Man… in his own person he killed the hostility. (Eph. 2:15) Last Sunday we begun to read Saint Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians which, in its opening verses, affirmed that God’s plan for creation is to ‘gather up all things in Christ’ (Eph. 1:9) and to make all believers to be his adopted sons in the Lord Jesus (Cf. Eph. 1:5). Following on from that, today we read that by restoring all things, and by making us his siblings, Christ is creating ‘one new single New Man within himself’ (Eph. 2:15), a new creation in whom barriers and hostilities are overcome. But as we read these verses with our twenty-first century sensibilities, we could be justified in thinking that there still is a bit of hostility left even if only in the way this passage is translated. Sons, man, and even a ‘New Man’… daughters and women seem all but unaccounted for. With this type of gender-exclusive language Ephesians may sound a little odd to many people, if not even infuriating who would regard these as gender-hostile words. Indeed, more recent Bible translations (such as the NRSV) propose a different take on Ephesians replacing “sons” with “children” and “man” with humanity”. But before we rush off to buy a more inclusive Bible, we might want to consider that here perhaps Paul is simply trying to make a theological point. When Paul writes about differences, and even hostilities, between people of different backgrounds and cultures he acknowledges a harsh human reality; that there are great barriers among the human family, often fuelled by ethnicity, culture, creed and many other reasons – including gender. But more specifically, Paul speaks of the barriers between his own Jewish people and the pagan world; between circumcised and the uncircumcised (Cf. Eph. 2:11); a marked separation between those who were accounted as God’s chosen nation and the rest of the world, the Gentiles – which included the people of Ephesus, and even us. However, after acknowledging the existence of these differences and hostilities, so strictly enforced by the Old Testament Law, Paul stresses the fact that every division (whatever it may be, or however unsurmountable it may appear) comes crashing down for Christians because in the Lord Jesus we are all gathered in the one body (his body!), regardless of our personal circumstances. Through the blood of his cross – spilled for both Jews and Gentiles – Christ reconciles believers to God and to one-another. In his crucified body our old selves (with our pride, squabbles, and vices) have also been crucified. In Christ self-offering to the Father we have become part of the New Man, a living sacrifice to God, which restores and brings peace to the whole creation. At the centre of Paul’s proclamation of the “Good News” (and indeed this is good news!) is a simple yet astounding belief; God sees each faithful as an adopted son, because he sees us in his only begotten Son Jesus Christ. Time and time again we encounter this concept throughout St Paul’s letters; later on in Ephesians the Apostle encourages all people to grow into the ‘perfect man, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ’ (Eph. 4:14); to the Romans and the Corinthians he writes that all the faithful form one body in Christ (Cf. Rom. 12:5 and 1Cor. 6:15); to the Colossians he advises to put to death the old man, or the old self – that is, those habits and dispositions which are incompatible with the gospel (Cf. Col. 3:5) – because they have been crucified with Christ… But perhaps Paul makes this argument nowhere more explicitly than when, using himself as an example, he says to the Galatians, ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me’ (Gal. 2:20). There is one hymn which also illustrates this point quite well and which I have quoted to you before, And now, O Father, mindful of that Love. In its second verse, praying to God the Father, it says, Look, Father, look on his anointed face, and only look on us as found in him. So, we are the ‘one single New Man’ in Jesus Christ. In this belief there is no judgment about where we come from, no belittling of our personal identities, no bias against equality, and no agenda to favour certain people over others. Surely, we each have unique personal qualities and particular quirks, our good habits which we should cultivate, and also our propensity to sinning which we should fight, yet the truth of the matter is that the Father chooses to love us not according to what each of us may deserve, but with the same unmeasurable love with which he loves Jesus, because we are one and the same in him. He even promises us heaven because that where Christ is. We are the ‘one single New Man’ in Jesus Christ. Then out of this flows a twofold vocation: first we ought to grow to full maturity in this new man; meaning that amongst ourselves there cannot be room for divisions or hostilities fuelled by pride, or by status in society, by wealth, gender, or anything else. God wills to restore all things in Christ, and Jesus reconciles us in his body, therefore we must be a people of peace; a people of welcome; a people of who foster reconciliation; and a people who bring hope. Secondly, we must reach out to those (and there are so many in our society) who think too little of themselves, who are trapped into thinking that for them there cannot be forgiveness or redemption; to those pressed down by social anxiety, or guilt, or worries about being able to fit in. We must reach out to them and bring them this good news; God loves us regardless of our failures or mistakes, he loves us because he sees us in his Son. Look, Father, look on his anointed face, and only look on us as found in him. … between our sins and their reward we set the Passion of thy Son our Lord. Amen. Amos 7:12-15 | Ephesians 1:3-14 | Mark 6:7-13

He has let us know the mystery of his purpose… that he would bring everything together under Christ, as head, everything in the heavens and everything on earth. (Eph. 1:9-10) This morning, both our first reading and the gospel give us a brief insight about of a possible cost for cooperating with God. First, we read how the prophet Amos is requested to leave a royal shrine (or even being banned from it) because his words of prophecy were too upsetting for the people hear; and then, Mark describes how the Twelve are told that, in certain instances, people will not welcome them. In both readings this personal cost is identified as rejection. Many people do not want to hear God’s words; they spurn his healing and the fullness of life he offers if this means giving up cherished habits; they do not want to change their way of life, and so they dismiss God. In so doing, they also reject those who cooperate with him. But although the cost of being a Christian is a clear theme in the Lectionary, I don’t really want to focus on it; rather, I would like to look at the positive aspects of cooperating with God; at those tasks we ought to do. Reading between the lines we see that in today’s readings Amos, Saint Paul, and the Twelve do something entrusted to them by God. Their examples give us a flavour of the jobs at hand… Amos proclaims the demise of a people who have forgotten the justice God had commanded them to practice, those who ‘trample on the needy, and bring to ruin the poor of the land’ (Amos 8:4); Paul writes words of praise about the blessings and the freedom which God bestows on those who accept the Lord Jesus (Cf. Eph. 1:14); and the Twelve set out to cure the sick and encourage people to change their way of life (Cf. Mark 6:13). To proclaim justice, to praise, to cure, and to encourage; these are just a few of the tasks God entrusts to those who endeavour to do their bit in bringing about his plan for creation. Yes, God has a plan. God has a plan, a purpose, (you could say “a goal”) for creation and he invites everyone to cooperate with him so that a new creation may come to fruition. In the letter to the Ephesians, St Paul affirms that God has revealed his plan in the Lord Jesus. This is an all-encompassing design that will include both heaven and earth; both the spiritual and material realms, so often seen at odds with each other. And his purpose is to ‘bring everything together under Christ, as head’ (Eph. 1:10). But what does it mean? Depending on the Bible translation you have at home, this verse may say something a little different. It could be translated as “to sum up”, “to unite”, “to gather again”, and even as “to restore” things to perfection. Out of all these possible meanings we see that God’s plan is that everything that exists might find unity in the Lord Jesus; a unity which was in him from the beginning of creation (because ‘all things came into being through him’ John 1:3), a unity that was lost, but that, once restored, it is going to be the hallmarked by justice, by peace, and by the joy of the new creation… And as God sets forth his plan he also calls people to work with him to establish it. So how can we see the restoration of all things in Christ for ourselves? How can we chip-in, as it were, and to do our bit in furthering God’s plan? I am sure we can all think of ways in which we can minister to one-another, serve God within his Church, and feel like we are doing enough. Yet, gathering all things in Christ goes beyond this. It means working to unite and to restore everything to the sovereignty, centrality, and primacy of Jesus. It means intentionally transforming our communities by asking ourselves (first) and (then to) those around us to let go of individualistic attitudes and self-centredness, so as to direct our every attention, and every effort towards Jesus. At the beginning of the twentieth century, at a time of some political turmoil, a saintly Pope, Pius X, wrote that all Christians, have a vocation to restore all things in Christ, and therefore they must ‘seek to restore Jesus Christ to the family, the school and society... They take to heart the interests of the people, …endeavouring to dry their tears, to alleviate their sufferings, and to improve their economic condition by wise measures. They strive, in a word, to make public laws conformable to justice and amend or suppress those which are not so.’ (Il Fermo Proposito, (The firm purpose), Pius X, 1905) A tall order for the average Christians; that may be. But time and again the Scriptures show us that cooperating with God is not a task entrusted to the elites and to those evidently qualified for it. To proclaim justice, to praise, to cure, and to encourage; we see these tasks worked out in Amos, Paul, and the Twelve. To help those in need, to welcome, to teach the faith, to pray for others; we see such things and more in the lives of the saints. It is these people, that is to say, people like you and me, which God calls to cooperate with him.  Mark 5:21-43 One of the synagogue officials came up, Jairus by name, and seeing him, fell at his feet and pleaded with him earnestly. (Mark 5:22) This morning’s gospel could be interpreted in different ways. For example, the connection which the lectionary makes between the reading from the book of Wisdom and Mark 5 highlights the fact the death and illness are not part of God’s design for creation, and that as a consequence God destroys these conditions every time he meets them in Christ. Instead, I would like to reflect with you on a broader theme which runs through the whole story; the theme of faith in the Lord Jesus. Mark introduces two characters who approach Jesus to find healing; their situations are desperate and it would be easy to think that they both have lost all hope and so they go to Jesus thinking “Well, what do I have to lose!” But if we look closely to the text we see that this is not the case; and instead each character makes a statement of faith in Christ as soon as they approach the Lord. ‘Do come and lay your hands on her to make her better and save her life.’ (Mark 5:23) says Jairus; and ‘If I can touch even his clothes, I shall be well again.’ (Mark 5:28) says the woman to herself. For both Jairus and the woman faith is manifested by their words of trust in Jesus and by their actions. In other words their faith is manifested by the choice of approaching the Lord and trying to find healing through him. So, both characters give us an idea of what faith is; an assent and affirmation, a willing and intentional “yes” to the person of Jesus Christ and to his ministry. As you probably know, I have never been overly fond of evangelical hymns, but there is one which fits this story very well. It sings, ‘O happy day that fixed my choice on Thee my Saviour and my God’ and indeed, this was a happy day for Jairus and the woman who, by opening the doors to Christ, by willingly and intentionally placing their faith in the Lord Jesus, find in him more than they could have ever hoped for. Certainly, their assent is somehow costly in both cases. Jairus, a synagogue official, has to humble himself before a man who was often at odds with the Jewish establishment, and he must face the peer pressure of more orthodox groups. The woman with the haemorrhage must brave rejection and insults from the crowds who knew her to be ritually unclean due to her illness. Yet, whatever the personal cost they faced at the time, by intentionally placing their faith in the Lord both characters are soon rewarded for their decision; for their choice, as it were. So, how is it with us? Do we express our faith in similar terms? And when is the last time we have knelt and we have made and affirmation of faith like Jairus' and the woman's? When was the last time we said in prayer “Jesus, I trust in you”? In the old rite for the Mass, and in the Book of Common Prayer, when the congregation stands to say or sing the Creed, they begin with the words “I believe in one God”. In this church we say “We believe in one God”. Yet, when we say the Creed, Sunday after Sunday, we often blurt out the words without really thinking about what we are actually doing. The Creed is a powerful affirmation of faith, which should be a weekly renewal of our intentional “yes” to Christ… We stand we assume the posture of those who are ready and willing, and we reaffirm together both our individual and our corporate faith; we place our faith squarely and solely again in the one true God. In a sense, we could say, through the Creed we make a statement of faith much in the same way Jairus and the woman did in the gospel. If we do this in all honesty our faith will be genuinely revived, and we will find in God more than we could have ever hoped for. Each Sunday then, would be the “happy day that fixed our choice on our Saviour and our God”.  Preacher: Mother Janet Yabsley Ezekiel 17:22-24 | Mark 4:26- 34 ‘Such a large crowd gathered around Jesus that he got into a boat and began to teach them, using many parables.’ (Mark. 4:26) In recent years - and more particularly in the last few months - there have been many occasions on which people have gathered together in large crowds for the specific purpose of demanding change. The nature of these gatherings, and the kinds of change looked for, are variable - yet increasing in frequency. They are happening around the globe. They are usually a plea, in essence, for a more equal, just and participatory society for all, in one way or another. More than five years ago people gathered in great numbers to hear Malala Yousafzai deliver her now-famous speech, ‘One child, one teacher, one book, one pen - can change the world!’ a demand for education for girls in her own region, and in many other countries.* Just a few days ago the ‘silent march’ of people affected by the Grenfell fire tragedy focussed on very many different needs that require urgent attention - all highlighted in a single incident; but one with such far-reaching consequences. Without protest, radical change rarely happens. The prophets recorded in Bible history were the protesters of their day. Everywhere they looked they witnessed injustice and oppression weighing heavily upon the people. In visions and in divine revelations they received warning messages from God. These were their mandate to seek change at the highest level. The word of the Lord - delivered by the prophets to the king - should result in positive action. In today’s Old Testament reading we heard one of Ezekiel’s earliest prophesies. He found it hard to believe that he had been chosen to proclaim the word of God, but through him God’s plans to bring messages of hope to the people of Israel were extremely effective. Speaking at the time of impending conflict with Babylon, Ezekiel foretold the time when all nations would come together under God’s rule of justice and mercy - a kind of looking forward in hope. He painted an imaginative picture as a way of revealing God’s plan:- All manner of birds of many different species would flock to the tallest, most majestic tree in the land - the mighty Cedar. They would all find a place to rest in its branches. Just so, God’s kingdom of truth and righteousness is stronger than anything else in existence. All nations of peoples would find a home within this kingdom and live together in peace. In contrast, Jesus’ parable of the Mustard Tree proclaims a crisis of the first magnitude! God’s kingdom, heralded most recently by John the Baptist, is now actually here! It has come with the arrival of Jesus the Messiah. The tree, which began life as a tiny seed, has been growing since the beginning of the age, largely unnoticed. It has come to full stature whilst we have been blind to its presence. Out of something small and insignificant, something truly great has emerged. The message about it is urgent! It concerns the here and now. It cannot wait. For in the Kingdom, God’s sovereign power is effective in all human experience. When it pleases God to establish his kingly rule there will be judgment upon all the wrong that is in the world; victory over all the powers of evil; and (for those who have accepted God’s sovereignty) deliverance, and life in communion with Him. To seek the Kingdom of God is to make the doing of God’s will the supreme aim. And all this has echoes in the prayer, ‘Thy Kingdom come…’ Again in contrast to Ezekiel, Jesus does not use the mighty Cedar as his symbol for the Kingdom, but a small shrub, the Mustard. A member of the Brassica family, the Black Mustard flourished profusely in the wild around the shores of the Sea of Galilee, but was cultivated on a large scale for the oil from its tiny seeds. This was used mainly for medication and healing. Whilst fruiting the plant was quite succulent, low to the ground, and not strong enough to support birds in its branches. But at the end of the season after harvesting, the branches dried out in the fierce heat of the climate, and became brittle - rigid enough to support the many and diverse birds feeding on the multitude of insects to which it was host. Just so, Jesus’ power was in his weakness, reflected here in a parable that uses the symbolism of a tiny seed. He was not afraid to speak of his own vulnerability. But that is not an attractive idea to many who would prefer to see power in images of towering strength. The king of the heavenly Kingdom, however, is the Prince of Peace; full of mercy and loving-kindness; seeking the lost; friend of the outcast; servant of all. Within this framework, previously unquestioned popular notions of the ways of God are turned upside-down… ‘whoever does not receive the Kingdom as a little child will never enter it.’ One thing is clear - both Jesus and the prophets-of-old understood God’s Kingdom not as ‘Utopia’ - something unattainable, but as present reality. They also understood that it cannot come to fulfilment without the determination of those who seek it to draw closer to God in prayer. That is why Jesus made the crowds sit down and rest… ‘“Come away to a lonely place, and rest a while” …for they had no time, even to eat!’ Contemplation, adoration, thanksgiving; these things are the path towards trust in the true and living God; the only foundation upon which we can grow and continue to grow; and take our place in a more just, equal and participatory society for all**. * Malala Yousafzai - speech at her award ceremony Nobel Prize for Peace. ** A participatory society includes every person within the availability of its freedoms, rights, opportunities and protections, under a just system of law. 2 Corinthians 4:13-5:1

As we have the same spirit of faith that is mentioned in scripture – I believed, and therefore I spoke – we too believe and therefore we too speak. (2 Corinthians 4:13) The passage of 2Corinthians we read this morning opens with an explanation of why St Paul is compelled to speak about faith and about the Lord Jesus in the way he does; faith is so embedded in him and it is such a powerful force that he cannot but write, speak, preach, and labour in every possible way to explain it to others and to bring Jesus to everyone he meets. Paul quotes psalm 116 in its Greek text as his justification – I believed, and therefore I spoke – but he quickly starts to use the plural form to include on just himself, but also every Christian in Corinth, and in turn, to include every Christian soul throughout the ages. We believe, and therefore we speak should be our own justification too for talking about faith and the Lord Jesus to others. It’s easy for someone in a dog-collar to say that we should talk about faith, especially when people expect you to do so, or half-imagine you to be a God-botherer. Sayings such as “Religion should be kept private” and “One shouldn’t talk about politics or religion at the dinner table” are deeply engrained in our society and in the way we do things. So, I know who awkward that might seem for many people in the pews. But the truth of the matter doesn’t change, We believe, and therefore we should speak. And Paul gives a simple and practical pattern for the way everyone should learn to talk about faith. For example, when he speaks about hardships of the body, he is not doing so from a lofty height. He is talking from personal experience. Physically, Paul was not a very healthy person to start with, and even putting aside the persecutions he endured for the faith, the constant travelling, his daily work, and his ministry for the Church, must have frayed his body and tested his endurance to the limit. Yet, he says, that out of personal sufferings comes the knowledge that the Father, who raised Jesus from the dead, is at work within us. And it is out of this vulnerability and frailty we can speak all the more clearly and convincingly about faith. Later on, when Paul compares the human body to a tent fit for our earthly dwelling, he does so from the point of view of a serious traveller and – most of all – as a tent-maker… we know that when the tent in which we live on earth is folded up, there is a house built by God for us… in the heavens (2 Corinthians 5:1). The Apostle is able to draw links between what he does for a living (which in itself isn’t particularly Christian or newsworthy) and his faith; his daily life informs the way he believes and the way he can articulate his faith to others. Then we too could learn from Paul. How does our experience of testing or difficult times can shape the way we talk about faith? how can it encourage others in their trials? and how can our work or various activities ground the faith in our daily lives? But I should say more about today’s readings. Some years ago a priest friend of mine wandered into his central London church only to find that the vestry had been broken into and a few items had been stolen from it. After the usual phone calls to the police and churchwardens he robed and went to the altar to celebrate a midweek Mass only to find, to his complete surprise, that the gospel reading appointed for that day was, ‘Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moths …destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven …where thieves do not break in and steal.’ (Matthew 6:19-20) As Alanis Morissette would say, ‘Isn’t it ironic?’ Even from personal experience I can testify that such coincidences or clashes between what goes on around us and the lectionary are very common indeed. We could say that they are just mere coincidences, or be grateful to God for pointing us towards his Word at the times when perhaps we most need guidance and consolation. I believe that this is also what is happening today with our readings. Not even a fortnight since Jill’s funeral, the past week has brought fresh sorrows to our church family as Father Colin passed away, but as we come to church to celebrate Mass and to begin a new week together our readings remind us of our faith in the final victory of God over death. In the eyes of the world Jesus looked crushed, broken, and condemned to an undignified death, but through the testimony of the Scriptures and through the eyes of faith we know that his rising from the dead is what gives us hope for the future. Human experience has been radically altered by this. We are given a new, final end for our earthly journeying; that is, as our second reading says, to be “raised and put at the side of the Lord Jesus with the saints” (Cf. 2Cor 4:14). Like St Paul, we may feel the strain of sorrow and the weight of sufferings that we (or our loved ones) have to endure, but we ought to place our faith in and be comforted by the One who ultimately will see that things are made right. So …we know that when the tent in which we live on earth is folded up, there is a house built by God for us… in the heavens (2 Corinthians 5:1). |

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed