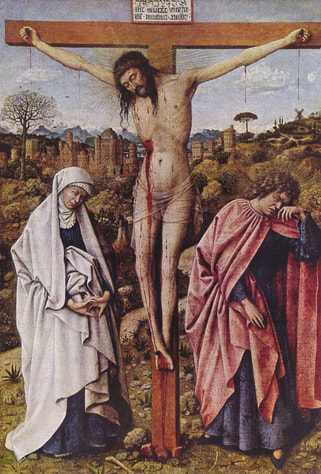

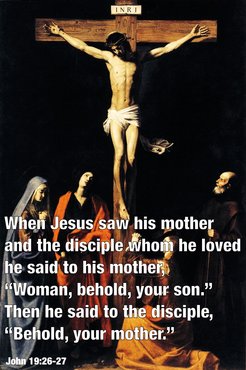

John 19:25b-27 Jesus said to the disciple whom he loved, ‘Here is your mother.’ And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home. (John 19:27). Mothering Sunday has a long tradition according to which the faithful would visit on this day their mother church – the parish church where they had been Baptised and received as sons and daughters of the whole Church of God. Today this tradition has largely been forgotten and the focus of the celebrations has shifted from the Church to motherly love in all its forms. Our gospel reading invites us to turn our attention towards Calvary to help us in finding the best pattern of motherly love in the most unlikely of places. As we look at the crucifixion scene we find the greatest example of motherhood in Mary, and, recapitulated in the Blessed Virgin, we also find all the unconventional mothers listed in the Scriptures. These are women who loved their children with boundless affection and trusted in God without any reserve. Among these remarkable women we find Sarah the mother of Isaac, Jochebed the mother of Moses, Hannah the mother of Samuel, and Naomi, Ruth’s mother-in-law. But if Mary is the best example of motherhood, why do our readings focus on such a terrible moment? Why do we have to look for a model of motherhood in such a desolated place as Calvary? Well, because it is in this place, at the foot of the Cross, that Mary is given by Jesus as “the” mother-figure for all people – not at Bethlehem, not at Nazareth or in the Temple, but on Calvary. At first, the whole scene may seem a little distant to our society that mainly associates pretty flowers, jewellery, and pastel colours for “Mother’s Day”. Mary is a widow whose Son has been condemned as an outlaw. Sharing in her son’s pain as only a mother can, she stays by the Cross, refusing to abandon Jesus. Her Son’s friends, many of whom she knew well, have all left apart from the youngest of them – John is little more than a youth. The adoring crowds who often stood between her and Jesus have gone as well. Those who are left do not care for her; they are there to bully her Son, to taunt Jesus even as He hangs from the Cross. Mary finds herself powerless, speechless at the impending, painful, undignified death of her only Son; her immaculate heart is broken, pierced just as Simeon had predicted when she presented Jesus to the Temple. But there is more, in these tragic moments Mary’ social position becomes even more precarious in a society that cared nothing or very little for women without male relatives. At the foot of the Cross, Mary knows that, once Jesus will draw his last breath she will find herself to be a nobody for ancient society. So, yes. Mary at the Cross does not exemplify motherhood in the most conventional, soft, and rosy sense we are so used to. But as we look closely at this scene, we can find faint echoes of it throughout history, even in our days; women whose love for their children is shown more often through the courage of their actions than through displays of affection; women doing all that is within their powers to be with their children no matter what the circumstances may be; and again women whose social position is determined only by whom they marry or who their sons are. As we look closely at this scene then we see that the challenging model of motherhood expressed on Calvary is able to speak to us all today too. But we ought to go a little further than this in looking at Mary’s motherhood, because even in this moment all is not lost. Mary may feel devastated and forsaken as she watches her Son. Yet, in this moment of absolute desperation, Mary’s motherhood is changed for good. As Mary feels that in losing her son she has become useless, God still sees her indispensable. In this profoundly dark night of her soul Mary receives from Jesus a new motherhood, the gift of a new son. John becomes her son, and with him Mary receives all followers of Christ in her care and embrace. At Calvary Mary is given as a gift, to all believers. So today, as we think with affection and gratitude about our own mothers and all the mother-figures we have encountered, the Church invites us to do a twofold task; to take Mary in our homes as our Mother as John did, and also to pray for those mothers who, like Mary, find themselves in difficult, painful situations. Today and everyday may we hear Jesus saying to us, Here is your mother (John 19:27). Amen.

0 Comments

Homily preached by Father Richard Peers SMMS at All Saints'. “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us …” It is, supposedly, the most famous opening to any book in the English language. Well, I have spent most of life as a teacher so I will ask you a question: can anyone name the book? Yes, of course, Dickens’ ‘A Tale of Two Cities’. “The best of times, the worst of times” seems to describe today’s readings. The account of the Transfiguration, the disciples see Jesus in glory, flanked by the Law and the prophets, represented by Moses and Elijah. The best of times. And the worst of times: Abraham taking his son out to the mountain top to offer him as a burnt sacrifice. I must admit to a great deal of fondness for Isaac, and not a little sympathy. I can just imagine the safeguarding forms that would need to be filled in now if a child came into school and described how his dad had taken him for a walk, gathered a fire, raised a knife over his head – and then sacrificed a handy goat instead! But safeguarding aside, imagine the trauma: your father is willing to offer you as a sacrifice, and not just offer, you but do the job himself, knife in hand, at the ready. Well, I suspect the account was never meant to be read quite so literally. But Isaac doesn’t interest me simply because of this bizarre incident in his childhood. Three other elements of this person who lived so long ago draw me to him. First of all, his name, Isaac. In Hebrew, literally ‘He who laughs’. I will come back to that later. Secondly, his faithfulness to his wife Rebecca. Isaac is the only one of the Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, not to have multiple wives. He lives a life much closer to Christian marriage than is common in the Hebrew Scriptures. I like that. In a time like ours that can seem to be the worst of times, when Christian marriage can appear to be threatened on every side and so many marriages end in divorce this is an important witness. Finally, there is one verse in Genesis 24:63 that makes Isaac significant for me. The translation is somewhat disputed but in the translation I like it reads: “And Isaac went out to meditate in the field toward evening.” What a wonderful image. This man, who has experienced the trauma of near-sacrifice at the hands of his father, whose name means to laugh, who is faithfully married to Rebecca: walking among his fields in the cool warmth of the evening, meditating. It is an image that reminds me of the first of the Psalms. Psalm 1 paints a picture of what makes for happiness: “Happy indeed is the man… Whose delight is in the law of the Lord And who ponders his law day and night. He is like a tree that is planted Beside the flowing waters, That yields its fruition due season and whose leaves shall never fade.” I hope that Isaac, who experienced that trauma, has found happiness, that as he walks in fields and meditates, he has deep joy and contentment. We all want to be happy. We want the people we love to be happy. “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” is even built into the American constitution. But whatever happiness and contentment Isaac felt as he strolled in that field so many centuries ago, would be complex. Whether it is meditating as you walk in the evening, sitting in the lotus position, reflecting, on the law of the Lord, or practising mindfulness of breathing; I am a huge fan of meditation. Spending time in silence is essential, I believe to a healthy life, to good mental health. When we meditate, when we still our minds, our inner states, as the inner waters clear all sorts of things float to the surface. In my experience and in the experience of most meditators there are two overwhelming sensations in this state. One meditation teacher (Chogyam Trungpa) calls it “the genuine heart of sadness”. We touch within ourselves a great tenderness. Not just in the sense of compassion but of sensitivities, our heart, our inner being is tender meat. It begins with ourselves, tenderness for and because of all that we have experienced, all the griefs and losses of every life. But soon we find our hearts expanding, tenderness for everyone that is alive because they too have experienced loss and grief. And in that knowledge, that we are all fellow-sufferers we can find forgiveness. We can forgive those who have hurt or damaged us because we can feel tenderness for them, our heart is big enough, open enough to do so. The only alternative to feeling sadness is not to feel, to harden our hearts, to narrow our hearts. Lent is a time for repentance and forgiveness. To turn away from sin. All repentance involves grief. The loss of something, the regret at things said or done, or unsaid and not done. All grief involves repentance. And all grief is permanent. All of us who have experienced profound grief at the loss of one close to us know that it has seared our souls, we move on, but it never leaves us. As Isaac walked in the field I hope that he felt that genuine heart of sadness, not paralysing grief but the positive sadness that is necessary for life and for forgiveness but also the others experience that is common to those who meditate: great and profound joy, a sense of belovedness, I hope that Isaac knew that Abraham had loved him and that he was beloved of God. That he heard, too the voice of the Lord. Just as on the mountain Abraham had heard it and on the mountain the disciples hear it. With God on our side who can be against us? St. Paul reminds us in the second reading. That sense of sadness and joy, which are inseparable is what can make us fearless, setting us free from anything that traps us and narrows our hearts. Our hearts are open, they are enlarged and tender when we are fearless, and we are fearless when we are in touch with sadness and joy. The spiritual writer Chogyam Trungpa writes: “this experience of sad and tender heart is what gives birth to fearlessness. .. Real fearlessness is the product of tenderness. It comes from letting the world tickle your heart, your raw and beautiful heart. You are willing to open up, without resistance or shyness, and face the world. You are willing to share your heart with others.” My prayer, dear friends, this Lent, is that each of us will open our hearts. That we meditate, like Isaac, and remember our griefs and touch our genuine heart of sadness in repentance and forgiveness, and that we will also touch the place of deep joy, of Transfiguration where each one of us, you and me, every one of us, will hear the voice of the Lord saying “You are my Beloved.” The best of times, the worst of times. To live a happy life is to hold those two things and not despair. This is the meaning of the cross, the fearlessness that Jesus has won for us because the crucified one is also the transfigured one. To know, as Jesus did on the mount of Transfiguration, that he was to die and suffer and be betrayed by the very people he loved, and still to stand. It is to be, like Isaac, the one who laughs, freely and fearlessly.  1Peter 3:18-22 ‘Christ himself, innocent though he was, had died once for sins, died for the guilty, to lead us to God.’ (1Peter 3:18) Lent has been, from its beginning, the time in which catechumens, the candidates for Baptism, prepared to be welcomed in the Church at Easter. And on this first Sunday of Lent our readings lead us to consider this sacrament as the beginning of the new life we share as Christians. Our second reading compares the sacrament of Baptism to the time when God saved Noah and his family in the ark, and gave them new life in the world he has cleansed from evil through the great flood. So too, at our Baptism the Cross of Jesus was our ark, and God saved us through waters of the font, giving us new life – but not new life in a world purified from evil as in the times of Noah, rather new life in his Son. Since our Baptism the life of Christ has been grafted in us and we have become part of that new creation God brings about in and through the Lord Jesus. This is why Saint Paul writing to the Corinthians says, ‘if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation’ (2Corinthians 5:17). So Lent should teach us that, if we are receptive to the grace of God, this new creation, this new life, will keep growing in us, transforming us into ever better likenesses, images of Jesus. Many aspects of Lenten liturgy (the colour purple, the sombre hymns, the silencing of the alleluias) call us to think about our failings asking God’s forgiveness for our sins and strength to rectify, if possible, our wrong decisions. But this is only the beginning of our Lenten journey; because essentially these forty days are given to us by God and by the Church to re-establish more firmly the life of Christ within us. We are not meant to metaphorically sit on a pile of ashes wearing sackcloth for six weeks feeling sorry for ourselves but actually do nothing to reverse our condition… Lent is a time to be active in the spirit and in the service of others. There are various schools of thought about Lent and about what one should or shouldn’t do during this season. The Church of England, being a broad church, keeps it nice and loose telling us that this should be a time of self-denial. But the substance of the matter is that the time-honoured practices of fasting, almsgiving, and prayer can be the source of great and unnumbered blessings as we enter the mystery of the Lord’s Passion, Death, and Resurrection and we prepare to renew our Baptismal commitments Easter. Through fasting, abstinence from certain foods, prayer, and charitable giving we do not exercise self-loathing or try to reproduce what Jesus went through on Calvary in some measly way. This should be quite clear to everyone – even though people outside these walls might make fun of the whole Lenten enterprise, or think of us a bit dim for denying ourselves things we like. Rather, by fasting and abstinence we aim to refresh the spirit and focus on our spiritual needs; by deeper prayer we aim to reconnect more clearly with Jesus; by giving to charity we aim to imitate the generosity of the Lord himself. And through all these Lenten practices together we aim to free ourselves of those old habits that have taken hold on us; we aim to spiritually die to sin in order to give space for the life of Christ to grow vigorously once again, until we can say with Paul, ‘it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me’ (Galatians 2:20). There is a beautiful hymn, “And now, O Father, mindful of that love” which puts these thoughts about being one with Christ in a neat verse. It says, Look, Father, look on His anointed face, And only look on us as found in Him; Look not on our misusings of Thy grace, Our prayer so languid, and our faith so dim; For lo! between our sins and their reward, We set the passion of Thy Son our Lord. Through Baptism we have become one with Christ. Lent calls us to make a genuine effort to move beyond ourselves, to rediscover our Baptism to find ourselves, our true identities, in Christ – in the one who leads us to the Father.  Leviticus 13:1-2, 44-46 Mark 1:40-45 ‘Feeling sorry for him, Jesus stretched out his hand and touched him. ‘Of course I want to!’ he said. ‘Be cured!’ (Mark 1:33-34a) The gospel presents us with a miraculous healing which ends up spreading Jesus’ fame as a healer and wonderworker to such a great degree that by the end of it people from far and wide come to seek the Lord’s help wherever he went (Cf. Mark 1:45). And out of this short story there are two key elements I would like to look at with you. First, let us look at the leper himself. We read that a nameless man suffering from leprosy (or more likely by an unidentified skin condition) approaches Jesus to ‘plead on his knees’ (Mark 1:40). He does not profess faith in Jesus in any explicit way, but his posture before the Lord gives away what he actually believes; in Biblical time, and perhaps even today, kneeling and/or bowing down was a manifestation of “worship”. This man somehow knows and believes that he is standing before the Son of God. And in him we see a person who comes to Jesus asking for healing with confidence about the Lord’s power and faith in him. St Mark doesn’t give us his name so that each of us could picture him or herself in his place, kneeling, pleading before Jesus; ‘If you want, you can cure me.’ Then, we should look at the issue of ritual purity. Last week’s gospel showed us how Jesus healed those who sought his help under the cover of night – probably because nigh-time was the only time they could have wandered around without being judged against the strict standards of Jewish purity laws. Today’ story follows on from that, by showing us yet another person oppressed by the sigma of being ritually unclean because of their illness, someone who had to live outside built up areas, had to warn others about his uncleanliness, and had to abide to the purity rules set out in our first reading. Undoubtedly, Jesus could have cured the man without even a word. But instead he chooses to reach out to the man and to touch him, jeopardising his own ritual integrity, and contracting the same social stigma by association. Why? ‘Feeling sorry for him, Jesus stretched out his hand and touched him. ‘Of course I want to!’ he said. ‘Be cured!’ (Mark 1:33-34a) Jesus feels sorry for him. Or, in a better translation, Jesus has compassion for him; Jesus in that moment is moved by the literally gut-wrenching feeling of compassion – “suffering with”. He reaches out to heal and to give the poor man that human contact which had been denied to him since the very first moment he had been pronounced unclean. But in touching the leper Jesus also shows that nothing whatsoever we could bring to or share with him could ever make him unclean – he has authority over illness, the law, and whatever stigma we can think of. On Wednesday we will enter the holy season of Lent. This time of spiritual renewal calls us each year to do two things; to return to God with all our hearts, acknowledging our sins, so as to discover anew forgiveness and freedom in Jesus; and also to exercise self-denial and charity so as to break bad habits, growing into the likeness of Christ. During this time our church will look increasingly sombre as the weeks will go by, we’ll put ash on our heads, a few of us will give up pleasurable things, and others will redouble their efforts in doing good works and in giving to charity. In all these things, it is as if we humbled ourselves before God, so as to move him to move his compassionate heart towards us, and through compassion to win pardon and grace. So, as we stand on the threshold of Lent, today’s reading teach us something about the season we are about to enter. First, as Jesus shows us that no illness can make ritually unclean, let us imitate him in the way we show compassion and reach out to others. Today, the Lord Jesus shows us divine healing powers which we do not possess, but the principle behind his actions holds true for each one of us. By imitating Jesus, striving to grow into his likeness, let us be moved to compassion towards those affected by the stigmas of our society. And in compassion let us reach out to heal. Secondly, on a personal level we are all like the leper who approaches Jesus; sin is something that not only we do, but something that pervades our society, something that we cannot cure ourselves. So during Lent let us approach the Lord Jesus with the same confidence and faith shown by this man. Let us fall on our knees and say to the Lord with one voice; “If you want, you can cure me.” Let this be our Lenten prayer – If you want you have the power to save me, my family, my neighbourhood, my world. Please, Lord, do it! ‘You shall not covet your neighbour’s wife.  This morning we come to the end of our Lenten journey through the Ten Commandments by looking at the last two instructions – “two”, if we use the traditional numbering, or “last one”, if we used the Anglican. ‘You shall not covet your neighbour’s wife. Neither shall you desire your neighbour’s house, or field, or male or female slave, or ox, or donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbour.’ (Deuteronomy 5:21) These last two commandments are precisely the reason behind my preference for the traditional numbering over the Anglican one, which tends to lump together people, animals, personal belongings, and everything else under the Sun in the same precept. In truth, there is a strong similarity between the two commandments, because both tell us not to unhealthily long after someone or something not available to us. But the Old Testament expressed this idea by using two distinct words in order to highlight the difference between the sense of desire we might experience towards someone else’s wife or husband, and the craving we might feel for something. Because, at the end of the day, a person (such as a wife) and a thing (such as a house or a field) do not belong in the same category and neither should the commandments controlling how we relate to them. The last commandment does mentions people, ‘you shall not desire your neighbour’s …male or female slave’ but only insofar as these servants – especially if numerous and capable – were seen as expressions of their master’s social status. So, the ninth commandment is primarily a call to refrain from lusting after a person not available to us; whilst the tenth commandment forbids us from wrongly desiring anything whatsoever another person might possess. By keeping them both we would go a long way in keeping also the preceding eight rules because healthy, or orderly desires, lead to sound actions as well. Conversely, failure to keep these two commandments can be understood in terms of the surreptitious vice of envy, or jealousy, which sooner or later will lead us to break the other commandments as well... But, if we were honest with ourselves, we would see that giving in to envy is a daily temptation for many of us – especially since we are surrounded by a culture where we are continually told that to be the object of envy is a great thing, a where envy of other people’s prosperity is the driving forces behind our consumerism, or at least behind most advertising campaigns. But we would do well to resist this temptation. Envy is unbecoming to a Christian, ‘for just as rust destroys iron, so too does envy destroy the soul that has it’ (St Basil, Homily on Envy). It is a dangerous spiritual illness that makes our greed to grow exponentially. Under its effects we come to desire inappropriate relationships with people not available to us, and to crave the possession of things that do not belong to us. Envy can also drive us to feel distress at the prosperity of others, resentful towards those people that this disease has wrongly made out to be our rivals, and even to feel cheerful at their misfurtunes. So what is the remedy against envy? And how can we keep the last two commandments? Sheer will-power can do only so much, but there are other two complementary ways to be immunised against envy. The first one is to take love as our yardstick once again. Loving our neighbours as ourselves will necessarily prevent us from coveting their fortunes in an attempt of making these our own. Furthermore, by loving our neighbours we will learn to exercise kindness, which is the habit diametrically opposed to envy. Instead of being distressed at the prosperity of others or happy at their demise, we will learn to ‘rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep [and to] live in harmony with one another’ (Rom 12:15-16) The second way to root out envy and to keep the commandments is learning to depend on God’s Providence. I spoke about this a few weeks back, but putting our ultimate trust in Providence is truly an essential tool for overcoming envy – if we really make God’s love for us the foundation of our existence, then no-one else’s wealth, husband, wife, or social status will ever cause us to be envious. And eventually we will be able to genuinely say with St Paul, ‘we brought nothing into the world, so that we can take nothing out of it; but if we have food and clothing, we will be content with these’ (1Tim 6:7-8).  This morning we continue our Lenten journey through the Ten Commandments, and because today we also keep Mothering Sunday, we take a step back to look at the fourth commandment (or the fifth in the Anglican numeration) ‘Honour your father and your mother, as the Lord your God commanded you, so that your days may be long and that it may go well with you...’ (Deuteronomy 5:16) This commandment opens what it traditionally considered the second table or tablet of the law; that group of instructions God sets out concerning our attitude towards others. This is because in most scenarios the very first neighbours we meet are the members of our own family, and within this “molecule of social life”, this mini representation of society, we learn to interact with and to love others. And within the family nucleus our parents hold a distinguished place as the ones who gave us life, nurtured us (in most cases), and looked after us from our conception. Therefore God, who ultimately gave us life through our parents, commands us to honour them, yes, and also to love and respect them, to care for them in their old age, and to cultivate a sense of gratitude towards them. In turn this obligation also expands like concentric circles to include siblings and relatives, the elders, and the leaders and fellow members of the Church. However, it is reasonable to say that many families are not exactly straightforward, and the fourth commandment acknowledges this by expressing what we have to do in the ‘positive terms of duties to be fulfilled’ (CCC 2198). In other words, this is not a prohibition such as ‘You shall not’ murder’ (Deut. 5:17) and then leave it at that. No, this is an exhortation to go a step further, and to do good regardless of circumstances. Indeed, the Scriptures remind us time and time again about the importance of our duties towards both parents and the elders. The book of proverbs is particularly good on this topic; for example, there we read, ‘Listen to your father who gave you life, and do not despise your mother when she is old’ (Prov. 23:22). In the book of Ecclesiasticus we read, ‘My child, help your father and mother in their old age, and do not grieve them as long as they live; even if their mind fails, be patient with them; because you have all your faculties do not despise them.’ (Cf. Ecclus. 3:12-14). But the ultimate teaching about this comes from Jesus when he condemns those who willingly withdraw their material support from their parents (Matt 15:1-9). But as well as duties, in this commandment we also read about a promise; ‘Honour your father and your mother ...that it may go well with you’ (Deuteronomy 5:16) St Paul points this out writing to the Ephesians (Cf. 6:2), and the promise attached to the commandment relates to our welfare as a society. So, showing true charity – that is care, honour, and devotion – to our parents has its own benefits, or its rewards, but not in the sense of immediate personal gains. Instead, for the commandment what we do and choices we make within our families have a wider impact, and have the potential of changing the world for the better, one family at a time. And by fulfilling our duty as sons and daughters, and by contributing positively to family life, we will promote harmony, concord, and peace in the wider society. Finally, let us turn for a few moments to the Gospel reading for Mothering Sunday, [and let us look at the scene represented here on the chancel screen]. This is the moment in which Jesus entrusts the community of believers, represented by Saint John, to the maternal care of his Mother – who from that moment becomes our mother as well. Yet, here Jesus provides us also with clear example about following the fourth commandment. Hanging from the Cross, the Lord spends the last moments of his earthly life in honouring his Mother. He ensures that Mary may find the security and stability often denied by ancient society to childless widows by giving her a new son, John, his beloved disciple. Thus, indirectly the gospel asks us, if Jesus could care for his Mother whilst suffering on the cross and close to death, what would prevent us from honouring our parents? Over the last couple of weeks we looked at the first three of the Ten Commandments and what they say about our relationship with God – how, how often, whom, and why we should worship.

Today we continue in our Lenten study of the commandments, and we turn our attention very briefly to the second half of the list; You shall not murder. Neither shall you commit adultery. Neither shall you steal. Neither shall you bear false witness against your neighbour. (Deuteronomy 5:17-21) Expressed all in the negative, these commandments look like a fairly straightforward list of prohibitions encompassing a limited number of offenses that finds a close parallel in our criminal system. Our laws too command us not to murder, not to steal, and not to lie in court; because committing any of these offenses would severely destabilise our society, and deprive victims of a few basic human rights. But the parallel between the commandments we find in the Scriptures and the regulation of civil society ends here. Because the commandments express much more than simple God-given regulations to help individuals get along with each other. Unlike in the case of criminal laws which command the respect of all subjects, the Ten Commandments are primarily the guidelines, or the if you will, regulating the covenant relationship between God and the people who belong to him through faith – meaning they regulate the relationship between God and us. Therefore, even in the case of commandments that prohibit us from harming others, God is still involved. And every time we break such a commandment we endanger our relationship with God, because God considers our relationship with him dependent on the ways we relate to our neighbours, not just on the ways we relate to him directly, through worship and prayer. But I say more. As Christians we must interpret these four commandments in the light of the Lord Jesus who, on one hand, gives us newer and more stringent regulations to follow such as in the Sermon on the Mount (Cf. Matthew 5:21-30); whilst, on the other hand, he encourages us to understand that love – and in this case love for our neighbours – is the only possible fulfilment for any commandment (Cf. Matt 22:39). This is why Saint Paul later writes to the Galatians saying ‘the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, “You shall love your neighbour as yourself”’ (Galatians 5:14); or again to the Romans ‘[the commandments] are summed up in this word, “Love your neighbour as yourself.” Love does no wrong to a neighbour; therefore, love is the fulfilling of the law’ (Romans 13:9-10) So, as Christians, our task is not simply to abide to the letter of the commandments and to refrain from doing evil; instead we are called to interpret them in a positive way, according to the royal law, ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’ (Matthew 22:39). In other words, keeping the commandments is a good place to start, but the Lord commands us to actively and intentionally do good. In this way the list of commandments could be expressed in a positive sense saying; You shall promote life. You shall live faithfully. You shall share. You shall speak truth. When we take in consideration all these things we can see that in the Ten Commandments God shows himself not as a distant referee who is ready to judge human relationships from a point of lofty neutrality. Rather, here God manifests himself as someone so deeply involved in our day-to-day lives as believers, that the moment we willingly transgress and hurt another person we necessarily wound his gracious love for us; and the moment we willingly do good for our neighbour we also do good for, and honour him. [At the end of all things] the righteous will say him, “Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?” And the Lord will answer them, “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” (Matt 25:37-40) This morning we continue our Lenten journey through the Ten Commandments, and we turn our attention to the third one;

Observe the sabbath day and keep it holy, as the Lord your God commanded you. For six days you shall labour and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God’ (Deuteronomy 5:12-14) Last Monday evening, as we begun the Pilgrim Course, we started with the simple exercise of remembering the Ten Commandments as a group, but try as we may, for a couple minutes we only managed to get up to nine. That is, until divine inspiration struck one of us and she said, “Keep the Sabbath holy”. But the forgetfulness of our little group about the third commandment is pretty much indicative of what has been happening for decades within the Church – the idea that corporate worship is somehow optional for a Christian coupled with changes to Sunday trading regulations have severely weakened the religious and moral obligation to attend Sunday worship, and particularly to attend a Communion service; to the point that many people have even forgotten (or never even heard) that there is a commandment about this. Yet, the commandment to observe the Lord’s Day and to keep it holy remains. Shabbat, the word from which we get the Sabbath, simply means “rest” and it connects us to the primordial origins of a day of rest found in the book of Genesis, when God is said to have rested on the seventh day, after having completed his work of creation (Cf. Gen 2:2-3). The Sabbath also embodies the celebration of how God later rescued the children of Israel from slavery at the first Passover, and it is still celebrated as such by the Jewish people. Both of these Scriptural events – God’s rest after creation and the redemption of Israel – form the backdrop to the new Sabbath, the new Lord’s Day, we keep as Christians. On Sundays we celebrate the salvation Christ won for us through his passion and death, and we rejoice in the new creation being inaugurated in him through his resurrection on the first day of the week. Then, how should Christians ‘observe Sabbath and keep it holy’? The third commandment does not require us to do anything extraordinary or convoluted. In fact, Jesus says, ‘The Sabbath was made for humankind, and not humankind for the Sabbath’ (Mark 2:27). And with this Jesus shows his followers that the point of the Sabbath is not to abide to strict regulations about precisely what to do, or how far one ought to walk, and so on. On one hand, to keep the Lord’s Day “holy” means precisely to set it aside, as it were, from normal or working days, in order to use the free time the Sabbath affords us to nurture our relationships with God and with his people, enjoying the company of the church family, and to recharge our batteries for the new week. Thus, Christians should not work on a Sunday, wherever that is possible and not essential; and we ought to avoid those trivial activities that deprive other workers of the Sabbath rest with their families – even if these should not be Christians themselves. On the other hand, to “observe” the Sabbath means to participate in the corporate worship of the people of God and to remember together the Lord’s redeeming acts for us all. This is particularly relevant in the celebration of the Eucharist, or the Mass, which is the everlasting memorial (the making present in our midst) of Jesus’ passion, death, and resurrection. But I think there is more to this. The Mass holds a special place in the Sunday pattern of worship as this is the only thing the Lord ever directly told us to do so that he might be present among us; ‘Do this in remembrance of me.’ (Luke 22:19) Do this. Not café church, or sweaty church, or praying at home, or whatever else. Jesus says, “Do this.” And as a consequence Christians have gathered on Sundays to celebrate the memorial of the Christ’s own Passover, which we now know as the Eucharist or the Mass, since the earliest times. Indeed, the Acts of the Apostles tell us this at several points saying that disciples “broke the bread” together every Sundays at the very least, in not more often. At this service we find ourselves gathered from every walk of life in the presence of the risen Lord as the new people of God. This is “source and summit” of our life as a Christian community; and it really should be regarded as the focal point of our week – the one thing we cannot do without, no matter what. Above all, the “this” the Lord tells us to do is the true fulfilling of the third commandment. ‘Observe the sabbath day and keep it holy, as the Lord your God commanded you.’ May we use this season of Lent to deepen our love and appreciation of the Mass, both on Sundays and on weekdays, so that through this sacrament we may grow ever closer to the Lord. Amen. Matthew 4:1-11

Jesus said, ‘You must worship the Lord your God, and serve him alone.’ (Matthew 4:10) Lent should be a time of spiritual renewal in which we ought to prepare ourselves for ministry in the world, like the Lord Jesus did before us, as he prayerfully fasted in the wilderness ahead of his public ministry. So I thought it might be good and useful for us to spend some time looking at the Ten Commandments together; and to shake the dust off form this core text of the Scriptures that many have forgotten or consider redundant. The list of the Commandments opens with a short introduction in which the Lord first reminds us about his relation to us. He says, ‘I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery’ (Deuteronomy 5:6) In saying this, God shows himself as saviour, as the powerful redeemer who breaks the bonds of slavery for those who believe in him. And this important reminder allows us to interpret the rules that follow, not as a mass of incomprehensible regulations limiting our freedom, but as the divine framework ensuring our flourishing as human beings, and our attainment of eternal life. Because God is the liberator of his people, he is not in the business of imposing laws as yet another yoke of slavery; rather he establishes the commandments so that we might find true freedom in following them. The First Commandment, ‘You shall have no other gods before me’ (Dt 5:7), may be initially thought just as a blanket ban on other gods. But, this is not all that the commandment requires from us. Instead this calls us to firmly centre our faith, love, and hope on God, with the intention of serving him alone. So, even though we do not believe in other gods, we ought to make sure we do not fall to the temptation to worship and serve something other than God, thinking that that something will bring us happiness and fulfilment. Maybe we have let material things to become our (inalterable) points of reference in life; be it an addiction, money, or possessions… Or maybe we have allowed other realities to replace due worship of God; things such as superstitions and indifference towards religion (which is always popular!). But in all these things, today’s gospel shows us what it means to keep this commandment whilst being faced by temptations; food, personal safety, and power can never come between us and obedience to God, because he alone is worthy of our service. The Second Commandment, ‘You shall not make wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God’ (Dt 5:11), could be easily interpreted just as a ban on blasphemy and swearing. But in reality, what is prescribed here goes beyond simply ensuring respect for God and preventing people from cursing him outsight. Instead the second commandment calls us to use carefully, and prayerfully, one of the most precious gifts God gives to those who believe in him – the gift of believing in his name. In the Scriptures God reveals his name, in an intimate way, only to his people; but even then, his name is only used in the context of worship, prayer, and blessing, because to speak God’s name means to confess and to call upon the constant, unchangeable being, …faithful loving and just, without any evil (Cf. CCC 2086) who is above all that exists. Likewise, the name of Jesus is most Holy, as St Paul says, ‘at the name of Jesus every knee should bend’ (Philippians 2:10), and similar respect should be observed when talking about the saints. A positive way to express this commandment could be ‘You shall honour the name of God as Holy’. Because this name and the realities connected to it are “set apart” and cannot be used in trivial matters or, as we do so often, as an exclamation. But there is more, remember how Jesus said in the gospel a few weeks back, ‘Do not swear at all… Let your word be “Yes” if you mean Yes” or “No” if you mean No”’ (Cf. Matt 5:33-37). This is because to take an oath falsely, or to make a promise I do not intend to keep, in the name of God is to ask God to be witness to my lie, bringing dishonour upon him. Far from being redundant, the first two commandments should help us reflect on what it means to be in relationship with God. Do we perceive what is being asked of us as Christians to be a burden? or do we consider serving God as a loving response to him for calling us to be his people? |

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed